Fire has a prominent place in several Greek myths and is associated with several notable characters in Greek mythology, most famously with Prometheus, who stole fire from the Olympian gods. It had a practical, symbolic, and even elemental significance to the Greek mind. In practical terms, it was both extremely dangerous and extremely useful, if properly managed, for warmth and for crafts like metalworking and related technological advancement.

Symbolically, it often had a connotation of intelligence and also of destruction as well as, thanks to the useful properties just mentioned, life. Elementally, it was conceived as a basic force of nature and one of the four elements of nature—earth, water, air, and fire. These various connotations should be borne in mind when considering the significance of fire in the myths.

Three figures and related fire myths are especially important in Greek mythology:

Hephaestus

Hephaestus (pronounced Hef-eest-us) was the god of blacksmiths and fire. He was born of Zeus and Hera, the king and queen of the gods, but became hated by Hera because of his deformity and notorious ugliness—he was the only Greek god who was not handsome or beautiful—and Zeus threw him out of Olympus. He was famously lame, either from birth or as a result of the impact on hitting the earth after the long fall from Mt. Olympus, and he walked with a severe limp.

On the positive side, Hephaestus was renowned for his magnificent craftsmanship—forged in fire—including spectacular architecture, most notably the golden mansions of the Olympian gods; automata, such as the giant animated golden dogs that guarded one of the mansions; and arms and armor, most famously the marvelous shield of Achilles described in Homer’s Iliad (about the Trojan War). His workshop was under Mt. Aetna in Sicily, an active volcano to this day and the highest volcano in Europe. Accordingly, he has associated also with volcanos, indicated in his Roman name, Vulcan.

Hephaestus got revenge on Hera by giving her a beautiful golden throne which, when she sat in it, tied her down with golden cords so fine as to be invisible to onlookers. She was forced to stay bound to the throne until Dionysus got Hephaestus to agree to release her after getting him drunk. He did not release her, however, without a price: he demanded that Aphrodite—the goddess of love and the most beautiful goddess next only to Hera herself—be given to him in marriage.

Thus the ugliest god won the second-most beautiful goddess to be his wife. Aphrodite, perhaps not altogether surprisingly, was unfaithful to him, and Hephaestus exacted an act of revenge on her as well.

Prometheus

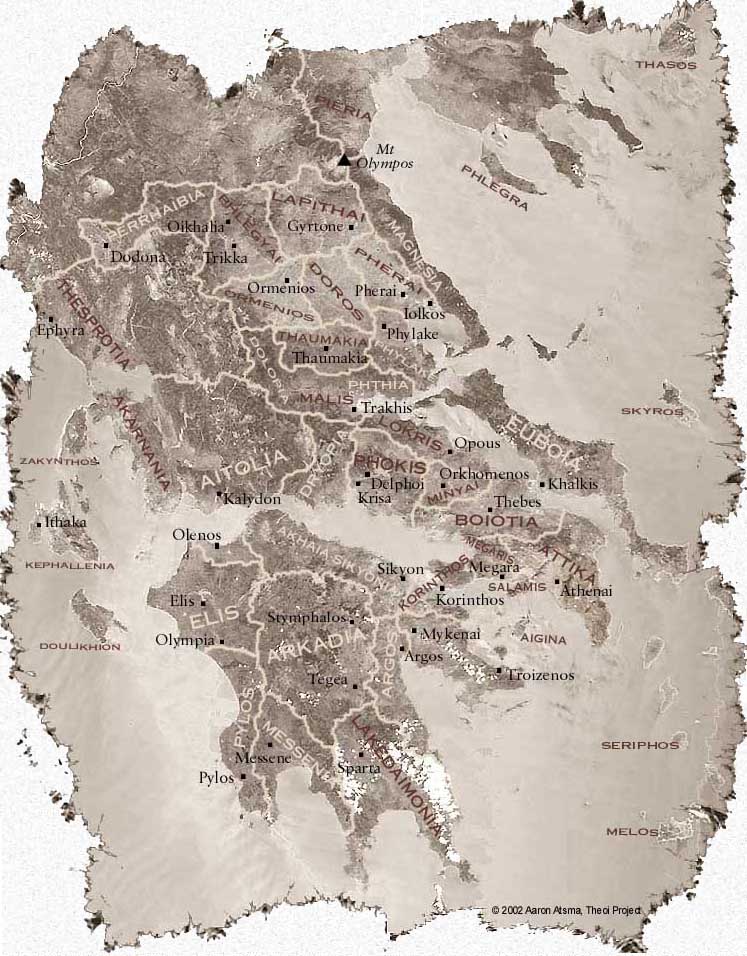

The myth of Prometheus’ stealing fire from the gods is one of the most famous Greek myths today and probably the most famous in specific relation to fire. Prometheus, whose name means “Forethought” or “Forethinker,” was one of the Titans, the gods who ruled the world before Zeus and the Olympians took over. Prometheus himself was treated leniently by the Olympians because he switched sides and joined them in the War of the Titans that culminated in the Olympian victory. (Most of the Titans were condemned to Tartarus or hell.)

Zeus gave Prometheus and his brother Epimetheus the task of providing gifts to mortal beings, who were as yet very feeble and struggling for survival. Prometheus was to bestow gifts on humans (in later versions of the myth he actually created humanity), and Epimetheus on the other animals. Unfortunately for humanity, before Prometheus was able to act, Epimetheus (whose name means “Afterthought”) gave all the best gifts to the animals (beauty, strength, speed, and agility, etc.), so human beings remained weak and vulnerable against the more dangerous animals and the rigors of nature.

This is where the fire myth comes in. Prometheus thought the least Zeus could do was to give humanity fire for warmth and material advancement, but Zeus refused. Prometheus, who was known to be a master trickster, had played a trick on Zeus, and Zeus in reprisal decided to punish mankind, whom Prometheus loved, by denying them the gift of fire.

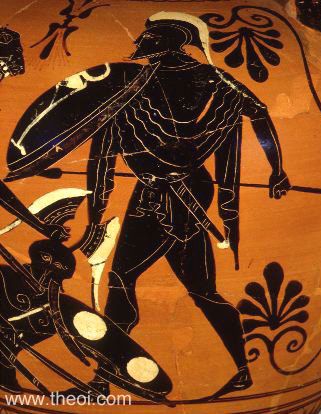

So, Prometheus snuck into Hephaestus’ workshop and stole fire and also forging implements and gave them to the humans. (Other accounts have him stealing the fire from Olympus.) Prometheus is therefore remembered as one of the great benefactors to mankind.

Zeus’s response was now even more severe. He punished humanity by sending them Pandora’s box full of untold pains and miseries, and Prometheus’ less intelligent, afterthinking brother Epimetheus foolishly opened the box. As for Prometheus, Zeus had him bound to a rock where an eagle feasted on his liver every day for many years.

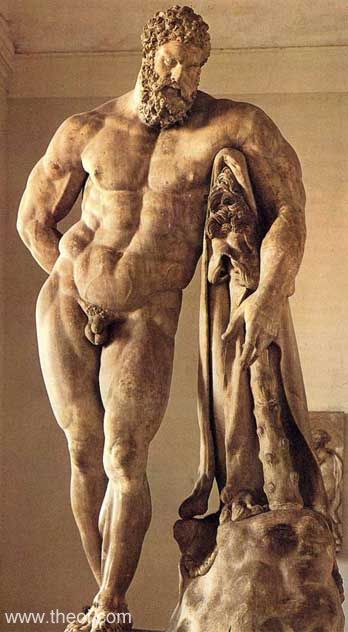

Zeus made his liver regenerate every night so the next day the eagle could go back to his feasting. Prometheus remained in this agony until finally freed by Heracles (Roman name Hercules). But the gift of fire was never taken away, and thanks to Prometheus’ gift were able to work their way out of their wretched physical condition.

Although he was a god, Prometheus’ theft of fire later became a symbol for human independence from the gods and eventually, in the context of the Christian West, of revolt against God in the form of atheism. Marx used the Promethean myth in this way, for example. More broadly, Prometheus still is used as a symbol for human intelligence, ingenuity, and progress.

The Phoenix

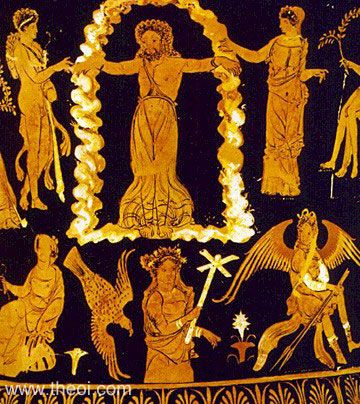

The Phoenix is probably even better known today than the Prometheus myth, though it may not immediately be associated in everyone’s mind with fire. There are versions of the Phoenix myths in several cultures in several civilizations. In the Greek version is the story of a bird of paradise, majestic in size and dignity and brilliant in color, who lives in paradise 1,000 years (though some sources put the time period as significantly longer or shorter) and then comes to earth and dies by fire, only to be reborn from the ashes to live another 1,000 years.

This cycle of life and death continues endlessly. In some versions, she is consumed by fire from a spark sent from the heavens; in others she sets herself on fire. Then after three days she comes alive.

The Phoenix is a powerful symbol, then, of life, death, and rebirth. As a symbol of rebirth it is also a symbol of hope. The Greeks associated it not only with the cycle of life in general but also specifically with metempsychosis or reincarnation. Thus they also connected the Phoenix with the idea of the immortality of the soul. Christians later employed the myth as a symbol of Christ’s death and resurrection.

As you can see, the significance of Greek mythology fire is very rich and varied, abundant with mystical as well as material overtones. As a symbol, it provides a way for us poor humans to conceive of our relation to nature, our ingenuity in the use of it, and how we can live well in the world.